10 mistakes that quietly kill returns — even for experienced investors

Typical patterns that repeat in portfolios of funds, angels, and syndicates

Losses in venture investing aren't an exception — they’re the baseline. According to various estimates, 70–90% of startups in investor portfolios fail to even return capital. Even in the public markets, only a small portion of companies generate the majority of total gains.

And it’s not just beginners making mistakes. Systemic missteps keep showing up in portfolios of funds, angels, and investment clubs — especially in overheated markets, with inflated entry valuations and growing competition for deals.

This article breaks down 10 recurring mistakes that quietly erode returns — even in professional portfolios. No generalities, no theory — just real cases, breakdowns, and practical takeaways.

1. Overfitting past success (pattern recognition overfit)

Experience can work against you. Especially when the goal is to find “the next Notion” or a “local Instacart.” The real issue starts when an investment thesis is built by blindly extrapolating the past — without digging into unit economics, market mechanics, or demand structure.

Case. AgriDigital (Australia) — an agri-SaaS platform visually reminiscent of monday.com, pitched as infrastructure for supply chain management in agriculture. Despite decent traction and scale, the SaaS metrics never held up: rollout took up to 9 months, churn was high, and LTV never closed the loop. The problem wasn’t the product — it was applying SaaS logic in a vertical where it doesn’t work.

2. Systemic local bias (your market, your expertise, your circle)

“I invest in what I understand” sounds like discipline. But in practice, it often means filtering out new information rather than managing risk.

Case. In 2019, WeWork invested in Wavegarden — a startup building artificial wave technology, with no link to its core business or strategy. The deal was pushed through by executives personally familiar with the founders. The investment delivered no upside and was shelved during restructuring.

3. Chasing signals and FOMO-driven entries

FOMO — Fear of Missing Out — drives many investment decisions.Rounds involving Sequoia, Benchmark, or Accel feel validated. But if you anchor on the brand, not the deal structure, the result is often the same: inflated entry and no downside protection.

Case. Builder.ai — a low-code platform for app development — raised $450M from Microsoft and Qatar Investment Authority. In May 2025, it filed for bankruptcy: Viola Credit pulled $37M from company accounts, leaving just $5M in cash. No amount of big-name backing can offset model flaws or governance risks.

4. Ignoring follow-on strategy and dilution risk

Follow-on means participating in future rounds (Series A, B, etc.) to preserve your stake (pro-rata), avoid dilution, and access better terms.

One of the most underrated risks in angel and syndicate investing is the absence of a follow-on budget — especially when entering at early stages.

Case. Clinkle (US) raised $30M at an early stage from Accel, Andreessen Horowitz, and others. Many investors didn’t join later rounds. The product never made it to market, and early stakes were diluted down to rounding errors. Complete write-off.

5. Chasing GMV and MAU instead of real unit economics

Even at later stages, investors often fixate on topline metrics — GMV, MAU, downloads — without evaluating operational quality. This is especially dangerous in sectors with long LTV curves like edtech, fintech, agtech, or health.

Case. Katerra, a construction tech startup backed by SoftBank, had impressive GMV and global rollout across dozens of markets. But: its unit economics never made sense, supply chains were out of control, and projects were structurally unprofitable. In 2021, the company filed for bankruptcy.

6. LP mindset where hands-on is required

An LP (Limited Partner) contributes capital to a fund but doesn’t participate in management.A hands-on model implies active involvement — helping the startup with hiring, strategy, growth.

Funds operate under a portfolio logic: 1–2 major wins offset the losses. Angels often mirror this model — but without access to allocation, control, or internal data. Same risk, less upside.

Case. Theranos: wealthy individual investors had no control, no information rights, and didn’t demand reporting. The result: total failure.

7. Underestimating governance risks

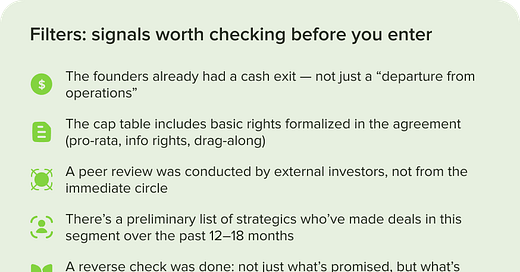

Governance risks arise when investors lack basic rights: access to information, anti-dilution terms, liquidation preference. In many club deals, the absence of formal agreements is still seen as “normal.” In practice, it leads to outcomes where even a successful exit delivers worse returns than later-stage institutional investors with formal protections.

Case. FTX: despite multi-billion dollar rounds and Sequoia’s involvement, governance was nearly nonexistent. No proper reporting, no transparency. After the collapse — near-total capital loss.

8. Confirmation bias: seeing what you want to see

Confirmation bias is when an investor notices only the data that supports their expectations — and filters out warning signs.

The closer the topic, the stronger the risk of projecting. When a founder reminds you of yourself, emotional attachment replaces analysis. This is especially common among founder-investors who “see their past” in the startup.

Case. Quibi — a mobile video-streaming venture by Jeffrey Katzenberg. Backed by investors swayed by his Hollywood track record. Product issues, weak retention, and poor demand were overlooked. Shut down within six months. Total loss: $1.75B.

9. The exit illusion

Many deals come with the thesis: “There’s always a strategic buyer in this space” or “This is a textbook acqui-hire.” But M&A activity is cyclical in most categories. Betting on an exit without validating demand is just betting on the market, not the business.

Case. Jawbone, a wearables company, was expected to be acquired by Apple or Samsung. That interest never materialized. The company went bankrupt in 2017.

10. Not understanding the logic of the funds you’re co-investing with

Syndicates and individual investors often join deals with funds — without understanding how those funds operate. How do they model IRR? What counts as a win? What's their plan if the deal stalls?

Case. Better Place — an EV infrastructure company backed by major VC and corporate funds. The problem? Each fund had a different exit plan. Result: misaligned incentives, a stalled round, and bankruptcy.

Counterexample: when everything clicked

Deal (mid-2020): a foodtech startup with a D2C product, thin margins, but a well-structured go-to-market plan. The angel syndicate demanded full transparency on gross margin and direct access to the CFO. By Series A, margin turned positive. In 2023 — secondary at a 5x.

Why it worked:

– Rigorous analysis before entry– Signed investor agreement– Follow-on strategy locked in early– Exit scenarios modeled in advance: M&A, secondary, or Series C growth

Conclusion

Losses aren’t an anomaly. They’re part of the stats. A fund’s IRR is built on a few wins and a long tail of zeros.

But most of the damage to returns comes from small mistakes — repeated systematically.

A good investor isn’t the one who never errs. It’s the one who builds a system that absorbs those errors and still maintains capital efficiency, even in volatile conditions.

If your model allows for mistakes — but prevents structural collapse — you’re on the right track.